How Human Urbanization and Light Pollution are Exterminating Nocturnal Pollinators

By William Qiu

Original article:

Light pollution impairs urban nocturnal pollinators but less so in areas with high tree cover

Tanja M. Straka, Moritz von der Lippe, Christian C. Voigt, Matthew Gandy, Ingo Kowarik, Sascha Buchholz

When we think of pollination, images of bees and butterflies often come to mind. But have you ever wondered what happens to the pollination of plants and flowers when the sun goes down? During the night, pollination is still occurring, though not with the help of those insects. Instead, moths and other nocturnal animals take over and keep the cycle of plant reproduction alive. An increase in human urbanization has led to more and more streetlights and fewer and fewer trees, which has decreased moth populations. Moths are attracted to light sources such as our outdoor lamps because they mistake them for the moon and stars, which they use to navigate. This causes them to be “stuck” to the light cone. They may die from exhaustion or from predators, which can upend entire ecosystems at a large scale.

A scientific experiment by Tanja M. Straka et al. seeks to determine the relationship between an area’s tree cover density, impervious surfaces, and types of streetlights and an area’s moth abundance and species richness. The research team first hypothesized that more impervious surfaces would have a negative effect on macro-moths (larger, easier-to-identify moths) and that different tree cover densities and lamps with UV would strongly affect them as well. To conduct their experiment, the team chose 22 areas in Berlin, Germany with varying amounts of tree cover, impervious surfaces, and light pollution. To measure all the variables, they utilized a program called QGIS to provide geographical data on the landscape in Berlin. At each site, researchers would collect moths that were attracted to previously set up gauze-covered UV light bulbs and sedate them for storage and analysis. This was done at the same time per night and on days without a full moon to make sure that there was as little interference as possible.

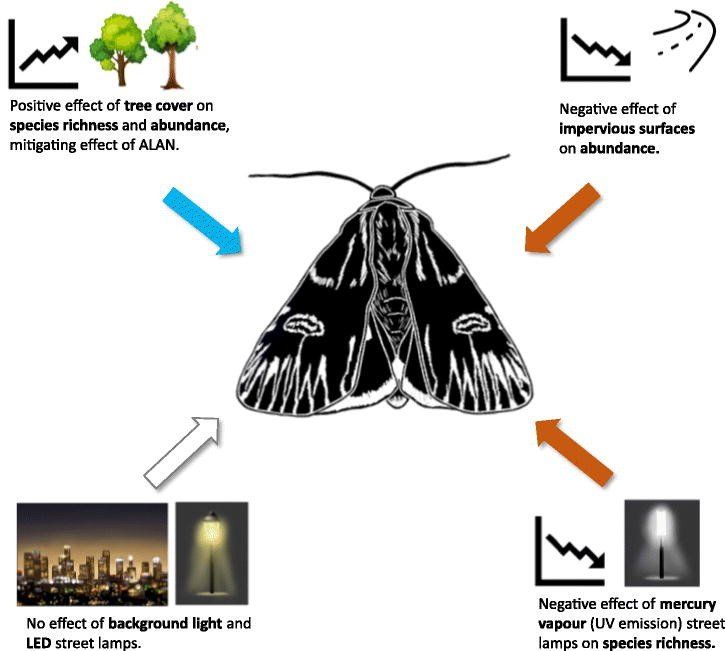

When examining all the macro-moths collected, most of the moths identified were from the Geometridae family, known as Geometer moths, and the Noctuidae family, also known as owlet moths. This figure by Straka et al. (2021) shows the results of the experiment by how each of the different area characteristics affected the moths.

As the research group predicted, areas with more impervious surfaces were more likely to have lower abundances of moths and areas with more tree cover were more likely to have species richness and abundance. It is interesting to observe that while UV emitting lamps negatively affected the moths, LED lamps and diffusive light did not affect the moths at all. This is supported by a research paper by Brehm et al., which found that “Moths are clearly preferentially attracted to short-wave radiation.” (Brehm et al., 2021).[1]

The research done by Straka et al. has given us more insight into how human urbanization has affected macro-moth populations. A key takeaway from the experiment is that by switching from the more harmful UV emitting streetlamps to LED lamps, we can keep our roads and cities less destructive toward moths while also saving money from energy costs. However, one thing that the research paper does not examine is the effect that LEDs of different wavelengths have on moths. The LEDs in the experiment were from 450-460 nanometers in wavelength, which would appear bluish to us. If the wavelength were varied and included longer wavelengths in the 600-nanometer range, there could be a change in the way moths are affected by the different colored lights.

The paper also brings up the fact that moths living in cities could be more situated to heavily light polluted areas and would not be as affected by light pollution. As Franzén et al. states, “This is likely because urban environments impose selection and constitute an ecological filtering process whereby species with certain traits might be favoured and better able to colonize and persist, whereas species with other traits are less likely to colonize and more likely to disappear.” (Franzén et al., 2020).[2] More studies will have to be done in dense city environments to truly understand how much our light pollution is affecting moths that still live in it.

References

Brehm et al. 2021 Mar. Moths are strongly attracted to ultraviolet and blue radiation. Wiley Online Library. [accessed 2021 July 20].

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/icad.12476.

Franzén M., Betzholtz P., Pettersson L.B., and Forsman A. 2020 Jun. Urban moth communities suggest that life in the city favours thermophilic multi-dimensional generalists. The Royal Society. [accessed 2021 July 20].

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2019.3014.

Straka T. M., Lippe M., Voigt C.C., Gandy M., Kowarik I., and Buchholz S. 2021. Light pollution impairs urban nocturnal pollinators but less so in areas with high tree cover. Elsevier. [accessed 2021 July 20].

https://www.journals.elsevier.com/science-of-the-total-environment.